Calvin Seerveld

In Memoriam

This past Tuesday, August 5, 2025, Calvin (Cal) Seerveld, passed into glory after 95 years of faithful service to his Lord and Savior. While I did not know him personally, having heard him speak publicly at Dordt once or twice over the years, in recent years I have been reading some of his work and finding much of value in his writings, especially as it relates to reading Scripture, understanding the importance of art, and his thoughts on Christian higher education.

As a reformational scholar and a friend of Dordt, a survey of his life and work seems fitting and valuable at this time.

I. Biography (borrowing heavily from this biography from Trinity Christian College)

Cal Seerveld was born in 1930, the son of a “fishmonger” and “household provider” (his terms), growing up on Long Island. From 1948-52 he studied Philosophy and English Literature at Calvin College. At Calvin, he studied under H. Evan Runner, the intellectual father of the reformational movement known in the 1960s as the AACS, an odd American student among the crowd of Canadians. On the occasion of Runner’s retirement, Seerveld noted the following:

Runner, it should be said, was not a solo act. He was a lead voice in a certain choir. [He then lists a litany of names and places, including Dordt.] Hebrews 11, you understand, is not a catalogue of "heroes of the faith." It is a list of misfits who were somehow faithful to the LORD's calling, who "won strength out of weakness," says the Bible, and did not live to see the fruits on their labours (Hebrews 11:32-40). They followed the LORD in faith.

…

The crux for us as the still living generation to not rip into tatters the tent of God's people we live in, but to keep the Reforming christian tradition we breathe and which has nursed many of us, keep its blood and sinews vital, supple, not diluted, so we not betray its winsome identity primed by the full counsel of God's Word: the critical point is to realize, as Vollenhoven was wont to say, that it is not a christian philosophy or worldview which holds us together, but the dedicated faith-commitment worked in our hearts to be joined by God's Word, to be driven by grace to be living out of Jesus Christ's resurrection, ascension and certain coming again, obeying God's ordinances with a holy spirit as an active saintly communion.

From Calvin, Seerveld went to the University of Michigan for an MA, followed by a five-year academic sojourn in Europe leading to a Ph.D. in Philosophy and Comparative Literature from the Free University in 1958, studying primarily with D. Th. Vollenhoven.

While in Europe he met Inès Naudin ten Cate, who would marry him in 1956. Together they had three children.

Returning to the USA, Seerveld taught for one year at Belhaven College, MS, before being recruited in 1959 to join the first class of faculty at Trinity Christian College in Chicago. He served Trinity for 13 years as a professor, department head, scholar, chapel speaker, and more.

In 1972, Seerveld moved to Toronto to join the faculty at the Institute for Christian Studies (ICS) as a Senior Member in Philosophical Aesthetics where he remained until his retirement in 1995. However, Seerveld continued to write and speak for the remainder of his life.

His wife passed away in 2021, but Seerveld continued to live in his home, possibly till very recently. He donated a large portion of his private art collection to Trinity Christian College and his personal library went to Redeemer University (Ontario).

Seerveld had a notable impact on Dordt during his long career. He came to Dordt on at least 10 occasions as a speaker. For his first engagement in 1965, he served as the commencement speaker for the first B.A. graduating class. His last event was as a First Monday Speaker in the fall of 2013. The latter talk, “How HOT is your Bible,” can be seen on YouTube. The provocative title is a common style for Seerveld. He has seven papers published in Pro Rege between 1987 and 2022. The Dordt Bookstore has 13 books authored by Seerveld and published by Dordt Press. Surveying The Voice and The Diamond reveals repeated references to Seerveld in the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s. “Enlaced,” the large steel sculpture at the east end of the green space between Southview, Covenant, and East Campus and designed by Professor Emeritus of Art Dave Versluis was inspired by Seerveld’s writings. Despite having taught at Trinity and living a stone’s throw from Redeemer, all three of his children graduated from Dordt.

To explore the themes of this influence, let me explore some of his writings that I have found informative and edifying.

II. The Kerygmatic Message

As a student of H. Evan Runner, Seerveld caught his vision for cultural criticism. His interest in literary theory would ultimately lead to a focus on aesthetics, but during his studies he toyed with the idea of ministry and put effort into learning several languages including Hebrew and Greek (for fun!). The result was some skill in Biblical studies.

So the first example of Seerveld’s scholarship focuses on the book How to Read the Bible to Hear God Speak. This book has a long history starting in the 1960s. The version I have was his first publication project with Dordt in 2003, but the third edition (or perhaps rendition) of the book (with different titles).

The book is a study of Numbers 22-24, the story of Balaam and his talking donkey. But the purpose of the book is to show Seerveld’s approach to reading scripture while contrasting it with other approaches. Seerveld describes his key principle as follows:

[O]ne needs to realize that the holy Scriptures are God-speaking literature given to us historically for our learning by faith the one true story of the Lord’s Rule acoming and the contours our obedient response.

…

So there are four elements fused in my biblical hermeneutical method, you might say:

(1) find the passage’s thread in the whole true story narrative of history as God reveals it;

(2) discern the literary configuration of the passage you are reading;

(3) win a sense of the historical matrix in which the section was booked;

(4) listen intently…to the convicting enlightening direction-message. [p. xii]

The kerygmatic message is that of the gospel, that Scripture at its core is the message that Jesus Christ is Lord, he loves us and died for us, and is alive and near us.

In this study, Seerveld interprets this passage using three common methods of interpretation:

A fundamentalist evangelical reading: a “straightforward, simple way” to get at the practical lessons that the passage teaches to “point us to heaven and keep us from the Evil One.” By putting scriptural words in front of the reader they will lead wholesome lives. But in doing so it misses the true message of a passage that is part of a much larger Bible and much larger story. “Numbers 22-24 is reduced to a mess of moralistic potage,” an oversimplified individualistic reduction of cosmic literature.

A higher-critical humanistic reading: higher criticism deconstructs the text to verify its historical accuracy and context, its reliability, and discovering any errors in the text. This text is not a genuine historical event in the life of Isreal, but a hodgepodge of texts brought together by a later editor. It is folklore; myth; saga. In doing so this approach recognizes the literary character of the passage and uses that character to aid the interpretation. At the same time, this approach too quickly tries to shoehorn a two-thousand year old story into modern enlightenment categories. Scripture becomes a “problem” of interpretation that begs for a solution and undermines one’s ability to trust its truth.

A scholastic, orthodox, dogmatic reading: here the reader is seeking to see the biblical truths found in a given passage that help understand doctrine and systematics of the faith. The prophecies clearly point to the Christ that is to come. Miracles are real. Infallibility (and possibly inerrancy) are affirmed. It recognizes that there is a big picture. But while it feeds the logical mind, this approach overlooks the yearnings of the heart. It also leads to monolithic thought where the doctrines become tests of orthodoxy.

In contrast to these three approaches, Seerveld offers his own approach, acknowledging that his method is not perfect and will not always lead to the right reading. Rather:

It is more relaxed too. It listens for the Good News, but in terms of direction rather than maxims; it honours research as an enriching factor, not as a precondition; it acknowledges that the message of the passage is given to be confessed, but then positively instead of apologetically, and fully rather than only in matters of dogma and morals. This other way of reading the Bible is born out of what we call a reformationally Christian perspective, and seems to me to do most justice to the riches of the Bible, letting its integrating, compelling, enlightening force work itself out on our whole life in society and God’s world.

One more insight:

The linchpin for reading the Bible in this Reformational Christian way is indeed to remember that the God-speaking literature given us historically with the overarching story of the Christ’s Rule acoming as book is meant to be heard. The Bible is a script to become oral. The writing by nature kerygmatic, a live telling, a proclaiming which asks those within hearing for a decisive response now. The Bible is the inscripturation of God speaking. (his emphasis)

III. Normative Aesthetics

Seerveld is an accomplished biblical scholar and a zealous cultural critic, but his main area of expertise is aesthetics. While other philosophers address aesthetic questions as problems for their analytical or comprehensive systems, Seerveld uses his art to unpack his philosophy.

I think this is illustrated in the last of his Dordt Press publications, God Picks Up the Pieces: Ecclesiastes as a chorus of voices (2023).

My NIV Study Bible describes Ecclesiastes as the commentary of an old man, probably Solomon, taking stock of the world. The author is called in Hebrew Qohelet, a teacher of an assembly. In my Bible, the text reads like a monologue of the author, flipping between poetry and prose. Headings largely describe the main idea of what is to follow. There is reference to Wisdom as a person speaking, but the text doesn’t set this character apart. Chapter and verse numbers slice up the text into manageable chunks.

Seerveld is an artist of words. He admits to have little skill in visual or musical arts (excepting some hymn texts). His studies have necessitated the mastery of several languages as well. This, along with his theological expertise noted above, means that in most of his writings he opts to translate scripture himself rather than rely on other translations.

So Seerveld decided to write a translation of Ecclesiastes. There is much in this book, so I will consider just a couple of items.

First, Seerveld observes that Ecclesiastes is a dialog. Yes, Qohelet is the primary character, but Seerveld identifies Wisdom, an editor, a couple apprentices, and a chorus (he says “refrain”). Seerveld writes a “readers’ theatre” version of this book. He creates an artwork (a stage play) out of this book. Gone are chapters and verses. In their place are character names in the format of a theatrical script. By putting the text on stage, the audience now gets to hear the dialogue and letting it stimulate their aesthetic sense, feeling the allusivity that is central to Seerveld’s aesthetic.

What this approach does is break down the text into a dialog rather than the utterly artificial verse structure. Now the text flows and the back and forth between Qohelet and the other characters and makes it much easier for the reader (or hearer) to follow the arguments. Yet he maintains that this is a formal translation, not an artistic paraphrase:

I claim that my rendering of the original Hebrew is not a “paraphrase,” like the brilliant work of Eugene Peterson’s The Message, but hews something closer to the original Hebrew text as “a translation.” Yet my translation wants the pungent grit of Luther’s rough-hewn German-folk version, open to the poetic imprint of judicious slang. [p. 2-3]

This leads us into my second point. I will let Seerveld speak:

For example hebel…is exactly right, imageic, and precise, like automobile exhaust. And it does not take much imagination to convert such obnoxious, wasteful, and gaseous fumes of hebel into a current borderline improper word like “fart.” So, rather than whitewash hebel into a philosophical denigration such as “absurd”…or “meaningless”…or even “enigmatic,”…I use “fart” for the disgusting falsity Qohelet disappointedly announces to be the possible vain (“vanity”) verdict for what all human effort amounts to. [p. 3]

Moreover:

The Septuagint translated [hebel] as…”a bombastic emptiness,” which the Vulgate turned into vanitas vanitatum [vanity of vanities], a critique of human pretension. “Vanity” has been taken to mean in modern times the affectation of importance men can falsely assume, or the primping of a woman before the mirror in her boudoir. But [hebel] is worse than human “vanity,” and is used throughout the Older Testament to refer to idols, to no-gods, fake deities, worthless puffed-up impotencies, which the Bible has no compunction against likening to “passing gas.” [hebel] means “a fart.” That’s the way the Bible pictures imposters of God—nauseous, gaseous, wasteful vapors like the enveloping choking exhaust which engulfs a pedestrian in the thick of massed idling cars in a traffic jam during rush hour on a clogged Toronto street. [Thus, in colloquial English, “vanity of vanities” really means] “The Most Enormous Puff Possible of Stinking Hot Air,” condemnably so! [p. 9]

So in Seerveld’s translation, the opening of Ecclesiastes reads as follows:

[The Editor speaks:]

Stinking hot air! Utter Nonsense! says Qohelet.

It’s all just a big fart!

What’s a person got left after all his or her hard work,

a person who does their damned best on this earth?

What’s left?

…

Everything, I tell you, every blasted thing—

a person can’t begin to relate them all;

no eye finishes seeing, no ear finishes hearing it all

—every thing is everlastingly,

exhaustedly busy moving…(where to)? (Eccel. 1:2,3,8) [p. 19]

Casting “vanity” as “fart” radically changes the mood of Ecclesiastes. Vanity is neat and clean, primped up and proper pompous pride. Farts are gross, and we don’t talk about them in polite company. Seerveld puts a different, and much less “beautiful” picture into our heads. A picture which makes us think and wonder. And that change in picture neatly leads us into his notions on aesthetics.

But first, if you were a student at Dordt in the late 1980s and you had anything to do with the arts, or just took Gen 200 (Core 160 in contemporary terms), you knew (or knew of if you didn’t do the assigned readings) Seerveld’s Rainbows for the Fallen World, arguably Seerveld’s magnum opus.

In Rainbows, Seerveld articulates his philosophy of art.

First, aesthetic obedience is part of the cultural mandate of Genesis 1:26 and 2:15.

Rather, the creation of God is unfinished, waiting historically to be uses; its variegated meanings are waiting there to be unleashed in a new chorus of praise for the Lord. This is our human calling…

That is where art comes in. Art is one way for men and women to respond to the Lord’s command to cultivate the earth, to praise his Name. Art is neither more nor less than that. [p. 25]I’m trying to say that aesthetic life is not something sophisticated—that’s a humanist lie. Aesthetic life is integral to being human as building sandcastles at the beach and giving your children names. [p. 50]

Art need not be fancy or meet the secular ideals of “high art.”

Second, while art is essential, it is not a matter of salvation.

I must emphasize the setting to all my remarks once more: second mile Christianity. An obedient aesthetic life is a matter of sanctification and not exactly a matter of heaven or hell. But aesthetic life-obedience and tastefulness, for example, are not therefore as you like it, since it is a question of maturity or immaturity to the redemption of your…body-of-Christ life in this historical world being cultured by humankind. [p. 61]

Art will ask us to slow down and ponder, while culture at large will press us to ever greater efficiency. The latter will cause us to become inattentive to redemption through art. As a corollary to the second point, one important example of immature aesthetic life: kitsch.

Kitsch means immaturity…(the cheap, for show, trinket affair)…

Kitsch trivializes human attention and sensibility, and God does not want that to happen. [p. 63]

The 1980s was all about kitsch—mass produced bits of décor that looked pretty, but also looked pretty cheap.

But what, you say, is art?

Seerveld rejects the notion that aesthetics is about some notion of beauty. The poetry of Seerveld’s rendering of Ecclesiastes is artistic and has a good aesthetic, but its references to the stench of farts is not beautiful. So beauty can’t be the kernel of the idea of art.

After years of careful, examining observation, my tentative answer goes like this: the decisive feature that turns photographic duplication of a face into art is allusiveness. [p. 126]

In the world of reformational philosophy, a concept such as “allusiveness,” upon being ascribed as the kernel of modal aspect such as aesthetic, becomes very hard to “define,” because kernels as kernels defy definition using other terms. Seerveld also uses “nuance” to get at the idea.

Some, like Dooyeweerd himself, use “playful harmony” to get at Seerveld’s idea. The “fun” in “just for the fun of it” is in the ballpark, and “fanciful imagining” or “humorfulness” round out Seerveld’s suggestions.

When all this (and more!) is taken over into the world of making artworks, Seerveld says, “Art is the symbolical objectification of certain mean aspects of a thing, subject to the law of allusivity” [p. 37 of A Christian Critique of Art & Literature]. When Seerveld uses farts, he is using them as a symbol of the meaninglessness that Qohelet laments. The text is the art. Farts are symbolic of the idea of meaninglessness because the idea of a fart points us to the grotesqueness of the lament.

IV. Cultural Criticism

Seerveld was not too concerned with being a bit vulgar in his writings. And sometimes he did not worry about his audience either. This often comes out when he is looking at the culture at large, beyond the fences of aesthetics and Biblical studies.

In 1970, he was one of several AACS related authors on a little book titled Out of Concern for the Church. For over a decade the AACS had been travelling across North America speaking on the ways that culture at large was broken and chastising the CRC for doing too little to fix it.

Well, this AACS group decided to put their thoughts together in one book. Hendrik Hart provided the most scandalous missive discussing the “wet dream of self gratification” [p. 32]. Seerveld was more reserved, but no less provocative.

My modest proposal for reforming the Christian Reformed church in North America is this: Close Calvin Seminary. Disband all denominational boards and standing committees. Strip yourselves of ministerial status; and let the ruling elders in the congregations designate as instructors in the Word whoever can bring the Word of Life from the Scriptures and is practicing a daily walk of prayer and fasting in the spirit of the Gospels.

…

To get the Christian Reformed church moving biblically as a reforming leader in North America will take an explosively radical, communal act of faith by its leaders… [p. 47]

What a challenge! How Baptist of them! Are you Pentacostal?!?

Like the other essays in this book, Seerveld is observing culture at large and coming to the conclusion that “we are in the twilight of Western thought, in the throes of something big going to pieces: the religious dynamic which has propelled our civilization is being found wanting” [p. 48].

In the CRC, “we carefully orthodox, Bible-confessing regular churchgoers are fundamentally hypocrites because the discipleship of Jesus Christ and the Kingdom vision of Paul and the prophets has not been proclaimed with power, ingrained in our minds and hearts by our pastors,” and fighting the wrong enemies [p. 51].

So toss the bums out and go out into the world and get our hands and feet dirty as we proclaim Christ’s Kingdom vision.

31 years later the CRC still has pastors and Calvin Seminary. In 2001, Seerveld gets invited to Dordt to give a talk on “What do a Reformational Christian philosophy and Christian Reformed theology have to do with one another in developing Christian scholarship?”

He’s calmed down a bit by this point since his was then 71 years old, but he still likes to rock the boat. He also knows he is speaking to an audience with a worldview like his own. Even so, his first major point explains a nuance that has vexed me for a long time.

When asked what we were doing in philosophy, I said, “We’re just being Reformed, biblically Reformational,” you might say. That is, not “Reformed as past tense, but as an active, ongoing Reformation of life, including thought, word and deed, honing it all to be true to the Scriptures. That was when I defined the term in this way:

“Reformational” identifies

(1) a life that would be deeply committed to the scriptural injunction not to be conformed to the patterns of this age but to be re-formed by the renewal of our consciousness so that we will be able to discern what God wills for action on earth (c.f. Romans 12:1-2) and

(2) an approach in history to honor the genius of the Reformation spearheaded by Martin Luther and John Calvin…, developed by Groen van Prinsterer and Abraham Kuyper…, as a particular Christian tradition out of which one could richly serve the Lord; with

(3) a concern that we be communally busy reforming in an ongoing way rather than standing pat in the past tense (ecclesia reformata semper reformanda est).

(Side note. This definition was originally written for his book analyzing the story of Balaam and his donkey.)

To be Reformed is to stand in the tradition of Calvin. To be Reformational is to be “the church reformed, always reforming” in the present.

This was his critique of the 1970s CRC. It was too stuck in the past, clinging to being idealistically Reformed, while neglecting the culture around them that was in need of that wisdom, but in a transformed way that speaks to the present. Two decades later this critique is still relevant, in my opinion.

With that introduction, Seerveld goes on to discuss three perennial problems relevant to Christian higher education.

What is the Bible?

“[a]ssuming that the Bible serves as 20-20 eyeglasses, lenses…, or a focusing searchlight, then if you just stare at the glasses…, you will miss its enlightening purpose. How does one put on the armor of the view-finding, penetrating Word of God…without just coming to look bespectacled?

“Christians who are dedicated professionally to serving students need, I believe, to become thoroughly at home in the Bible, honoring its historical, literary, and proclamational nature.

…

“So the Bible is not a source book of proof texts, but a network of connected passages coloring the Lord in a rainbow of awful glories.”

So that “the Bible provides the a priori for searching the world we live in rather than letting the present culture set the standards…”Christian Historiography and Philosophy

“since college education like all human culturing happens communally, can we follow through on the unity we have in Christ—past a holy daily way of life and world-and-life vision that we cultivated in God’s world for Christ’s sake—into the very fabric of our vocation, namely considered reflection on what, how, and why things mean what they do, on what has taken place, and on what should be done?”

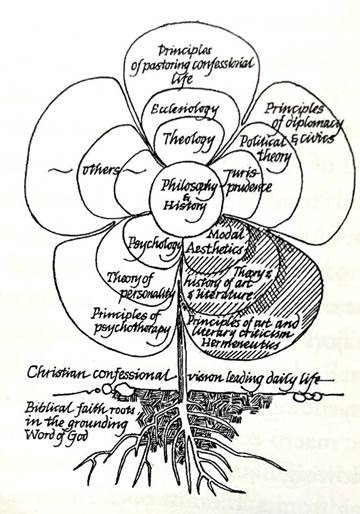

“but if a Christian college makes earnest with the thrust of the Reformation that we faculty members…are to wash each other’s educational feet with the conceptual, imaginative, verbal, and enabling gifts we have at our disposal…, and if there is a philosophical systematics deepening a Reformed world-and-life-vision that can help a college teacher test the basic categories one uses in one’s field, points one toward intersecting cruxes of meaning for several disciplines, provides a precise vocabulary to export the results of one’s special studies out of the strength of being one voice within a whole reflective communal chorus of teaching saints, then imagine what such a cross-disciplinary, resonating message from different classrooms will make upon students.”

That is, academic disciplines focused on developing and transmitting “serviceable insight” need a philosophical framework, like that of Reformational philosophy, as a bridge from fundamental biblical worldview to their disciplines, but also as a bridge between those specific disciplines. Then together the faculty will speak with a unified voice and students will hear the same message across the disciplines. (After which they grumble about all the times they hear about worldview, shalom, redeeming creation, and serviceable insight!)Higher Education, Apprenticeship in Holy Scholarship

“To be a scholar is to be schooled in studying something, disciplined, thoughtfully thorough in coming to know what you are doing or are discovering. “Higher education” at college is a special opportunity for a younger generation to taste and for an older generation to show-and-tell scholarship together…”

“College is the time of your life to be an apprentice scholar, even if you do not want to be a scholar for life…Students should not be hurried, must not have to be in a pell-mell hurry to get a job and make money. That is the hypnotic, crooked idea of time that American culture breathes—time means money. No! according to the Bible, time is a gift of God to be redeemed.”

“Consecrated studious thinking, imagining, speaking, writing, and reading is doing something and doing something is as important as a pregnancy: preparing with ‘serviceable insight’ for the birth of ‘insightful service.’”

He concludes with this caution:

One must not allow the Reformational Christian philosophy (or the Reformed theology) jargon ever to become mouthed shibboleths denoting kosher faculty…So I pray that you Dordt faculty keep the tradition of the Reformation alive, not let it become past tense.

Calvin Seerveld understands what Dordt is about because we are cut from the same cloth. While his voice is now silent, his ideas will continue to inspire and encourage well into the future.